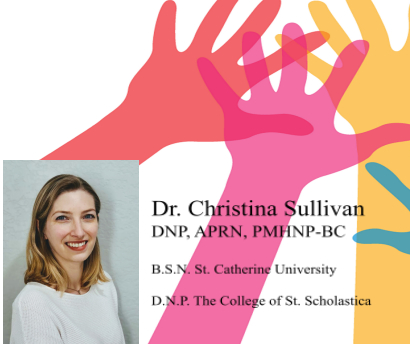

We are very excited to announce that Dr. Christina Sullivan, DNP, is holding weekly trauma-based group sessions. This group, “Overcoming Trauma” will take place on Zoom every Thursday from 5PM CST – 6PM CST starting August 12, 2021.

Who should consider joining?

If you have experienced trauma and are looking to develop skills in a supportive group setting to overcome the symptoms of PTSD.

What are the benefits of group therapy?

Group sessions are a very safe space for all involved. Each member is encouraged to interact with each other, but you are more than welcome to share as much or as little as you feel. Hearing feedback from your peers can open your mind to alternative viewpoints that may not be addressed in individual therapy. Group therapy challenges those feelings of isolation that can result due to trauma through creating a safe and cohesive environment.

How do I sign up for “Overcoming Trauma” group sessions?

If you are interested in attending Overcoming Trauma, or if you have any questions about this group, please feel free to email inquiry@telepsychhealth.com, call 888-730-5220, or you can go to the “contact us” section of this website and fill out the form.