Substance Use & its Effects on Sleep

Sleep…

100% of people do it

~100% of people take it seriously

And it has major impact on one’s health and risk of relapse.

Common misconceptions of sleep…

- People who fall asleep in meetings are lazy.

- Sleeping in on the weekends is enough to catch up on sleep debt.

- You can “train” yourself to get less sleep.

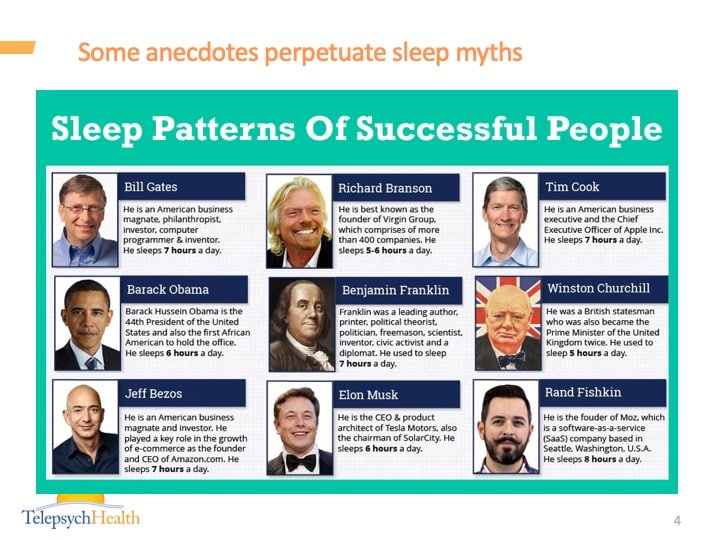

Some anecdotes perpetuate sleep myths, but, relatively speaking, we have come a long way.

500 BC Alcmaeon: Sleep is a loss of consciousness occurring when blood drains from the surface of the body, as sleeping bodies feel cool to touch.

350 BC Aristotle thought that sleep was a result of warm vapors arising from the stomach interfering with the heart, where consciousness arises.

162 AD Galen thought that consciousness arises from the brain

1584 Cogan goes back to sleep being brought on by vapors arising from the gut.

1619 Descartes believes soul arises from pineal gland

1700s Two phases of sleep starts to disappear after the industrial revolution*

1830 MacNish: sleep is an intermediate state between wakefulness and death

1879 Edison invents the light bulb, and average American’s sleep decreases 3 hrs

1899 Freud theorized that dreaming is a “safety valve” for the release of instinctual energy

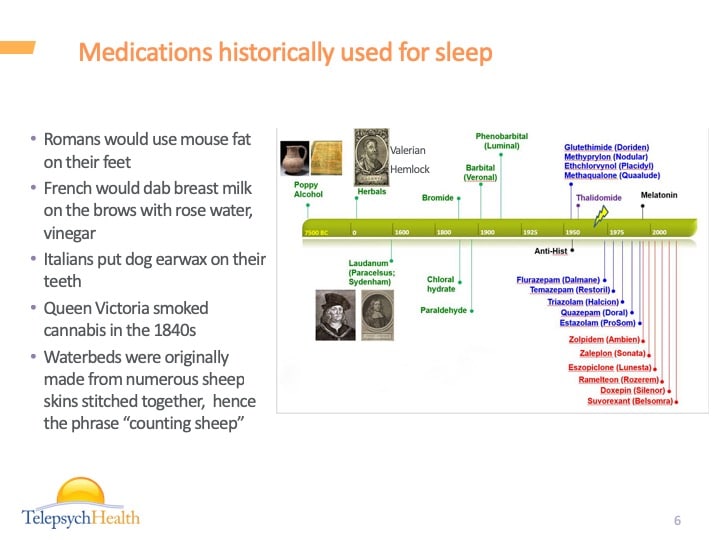

Medications historically used for sleep

Romans would use mouse fat on their feet

French would dab breast milk on the brows with rose water, vinegar

Italians put dog earwax on their teeth

Queen Victoria smoked cannabis in the 1840s

Waterbeds were originally made from numerous sheep skins stitched together, hence the phrase “counting sheep”

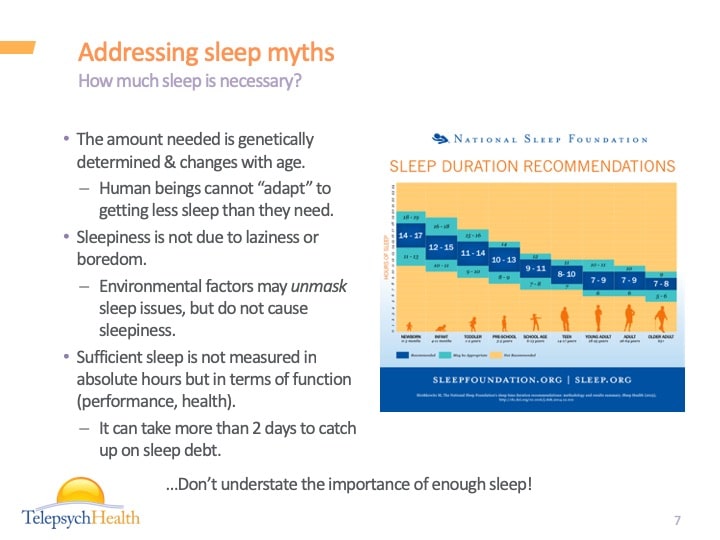

Addressing sleep myths

The amount needed is genetically determined & changes with age.

Human beings cannot “adapt” to getting less sleep than they need.

Sleepiness is not due to laziness or boredom.

Environmental factors may unmask sleep issues, but do not cause sleepiness.

Sufficient sleep is not measured in absolute hours but in terms of function (performance, health).

It can take more than 2 days to catch up on sleep debt.

Why should we care about sleep?

Hunger and Weight

Sleep deprivation leads to propensity for bigger portions, choosing high calorie high carb foods, and unhealthier foods

Increased risk of obesity over time

Cardiovascular Risk

Those sleeping less than 6 hrs per night had a 4x higher risk of stroke compared to their normal weight counterparts that were getting seven to eight hours.

Chronic sleep deprivation has been associated with high blood pressure, atherosclerosis (or cholesterol-clogged arteries), heart failure and heart attack, Harvard Health Publications reports.

Single night of partial sleep deprivation leads to insulin resistance.

Cancer

World Health Organization designated shift work as a Class 2A carcinogen: shift work is “probably carcinogenic to humans.”

1,240 participants who underwent colonoscopies found that those who slept fewer than six hours a night had a 50 percent spike in risk of colorectal adenomas

2012 study identified a possible link between sleep and aggressive breast cancers.

Researchers have also suggested a correlation between sleep apnea and increased cancer risk of any kind.

Immunologic effects

Carnegie Mellon study found that sleeping fewer than seven hours a night was associated with a tripled risk of coming down with a cold.

Pain

Sleep deprivation impairs endogenous opioids (endorphine) function, downregulates central opioid receptors, decreasing effectiveness of exogenous opioids

Attractiveness

Sleep deprived study participants were rated as less attractive and sadder, and judged to be less approachable.

Substance Use

Individuals who drink are more likely to have insomnia, and those with insomnia are more likely to drink.

Insomnia is a predictor of alcohol relapse in at least 17 studies.

Decreased quality of life and higher psychiatric symptoms.

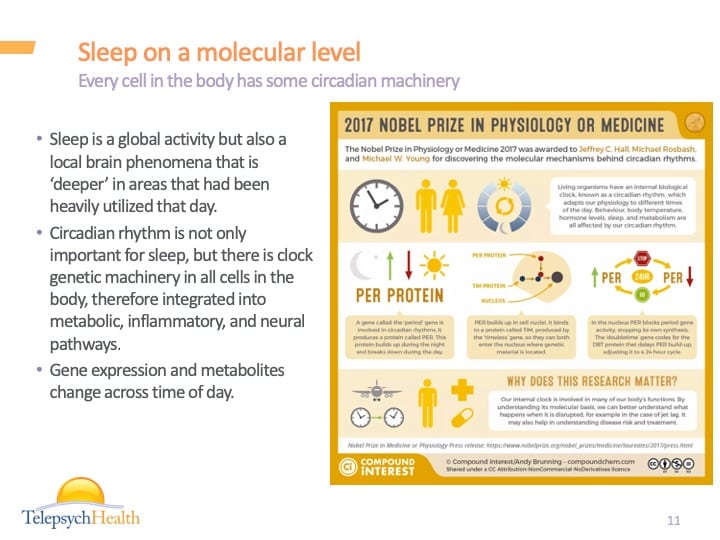

Sleep on a molecular level

Sleep is a global activity but also a local brain phenomena that is ‘deeper’ in areas that had been heavily utilized that day.

Circadian rhythm is not only important for sleep, but there is clock genetic machinery in all cells in the body, therefore integrated into metabolic, inflammatory, and neural pathways.

Gene expression and metabolites change across time of day.

Every cell in the body has some circadian machinery

What is normal sleep?

Regular bed & wake times

Fall asleep within 30 min

No more than 1–2 awakenings per night, <30 min each

(Knowing our evolution can put a different spin on this)

Wake up feeling rested and refreshed in AM.

>85% of time in bed is sleeping (sleep efficiency)

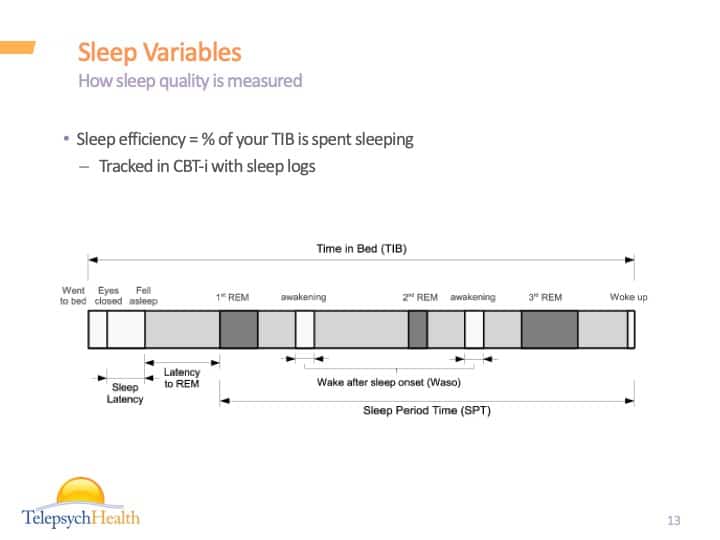

Sleep Variables

Sleep efficiency = % of your TIB is spent sleeping

Tracked in CBT-i with sleep logs

How sleep quality is measured

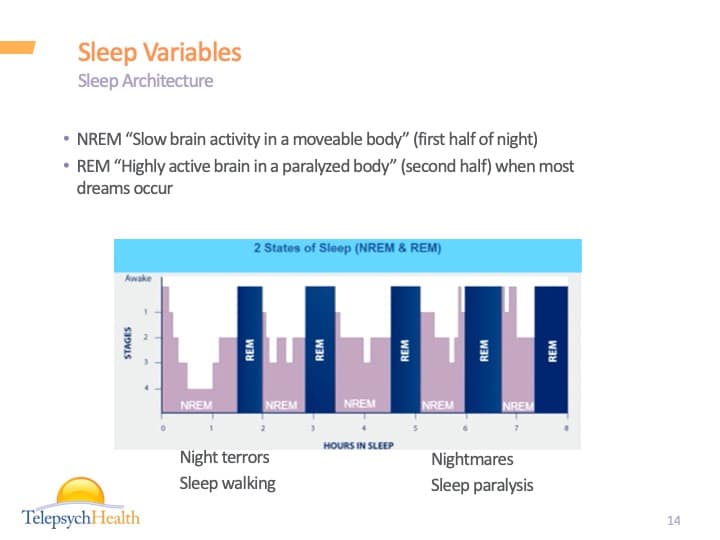

Sleep Variables

NREM “Slow brain activity in a moveable body” (first half of night)

REM “Highly active brain in a paralyzed body” (second half) when most dreams occur

Sleep Architecture

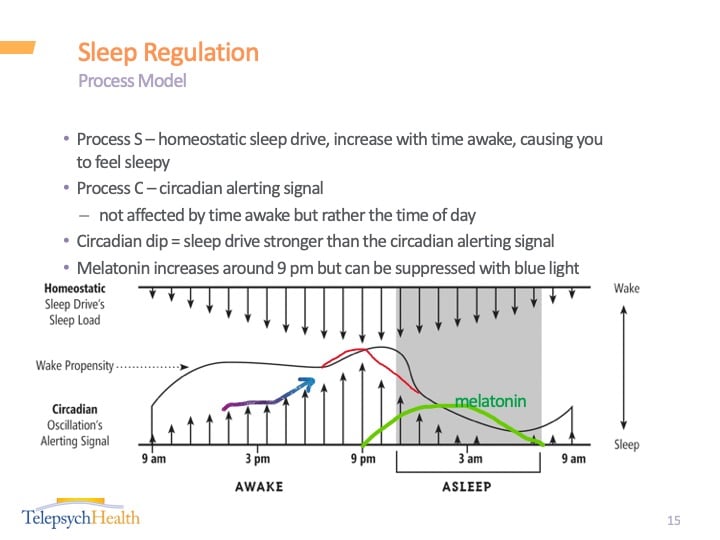

Sleep Regulation

Process S – homeostatic sleep drive, increase with time awake, causing you to feel sleepy

Process C – circadian alerting signal

not affected by time awake but rather the time of day

Circadian dip = sleep drive stronger than the circadian alerting signal

Melatonin increases around 9 pm but can be suppressed with blue light

Alcohol & Sleep

Insomnia is extremely common in those who drink (range is 36% to 91%)

Insomnia leads to drinking, and drinking leads to more insomnia.

Those with insomnia are 2.4x more likely to drink alcohol heavily (Ford & Kamerow, Crum, Weissman).

Those who drink alcohol heavily are 1.5x more likely to develop insomnia.

Insomnia is associated with relapse in over 17 studies.

Insomnia is associated with increased risk of suicidality & depression in those who drink.

Why is sleep important in AUD patients?

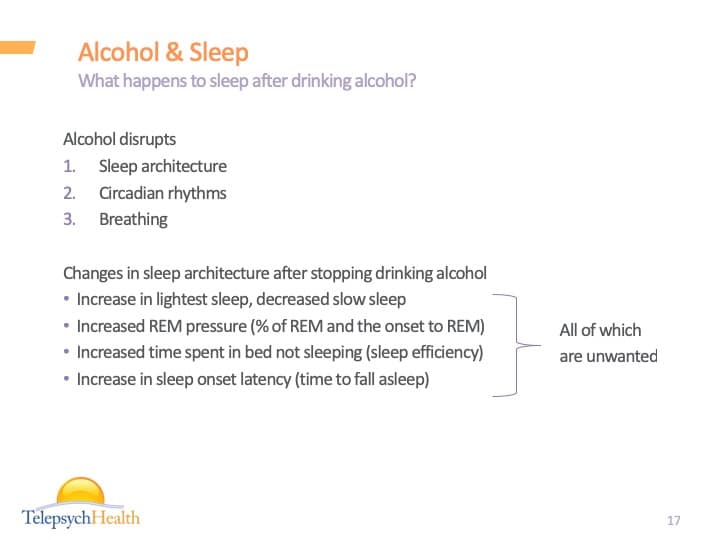

Alcohol & Sleep

Alcohol disrupts

- Sleep architecture

- Circadian rhythms

- Breathing

Changes in sleep architecture after stopping drinking alcohol

Increase in lightest sleep, decreased slow sleep

Increased REM pressure (% of REM and the onset to REM)

Increased time spent in bed not sleeping (sleep efficiency)

Increase in sleep onset latency (time to fall asleep)

What happens to sleep after drinking alcohol?

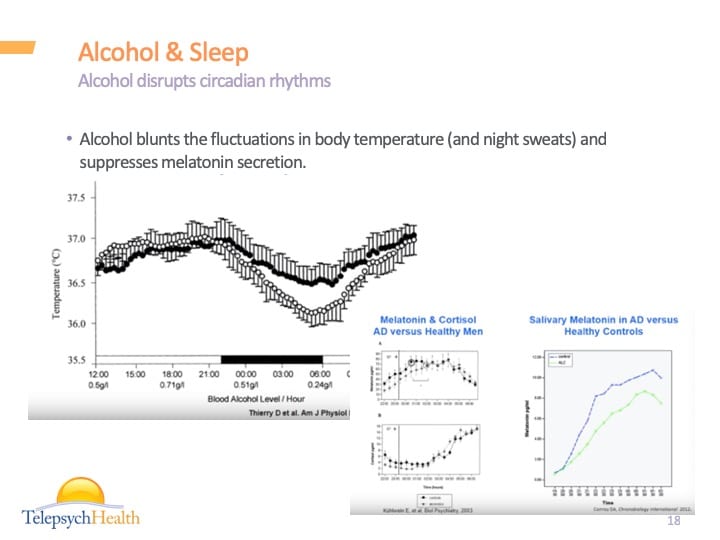

Alcohol blunts the fluctuations in body temperature (and night sweats) and suppresses melatonin secretion.

Alcohol disrupts circadian rhythms

Alcohol was shown to cause higher apnea hypopnea index with alcohol (compared to placebo), and decreased oxygen saturation difference (compared to placebo).

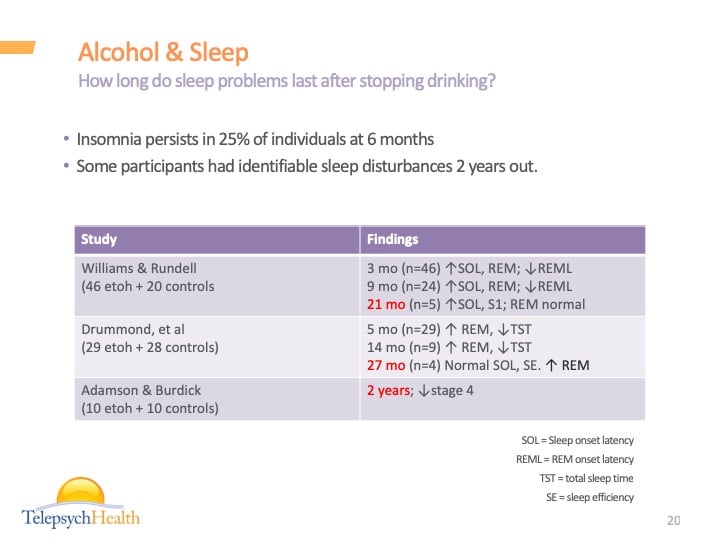

How long do sleep problems last after stopping drinking?

Insomnia persists in 25% of individuals at 6 months

Some participants had identifiable sleep disturbances 2 years out.

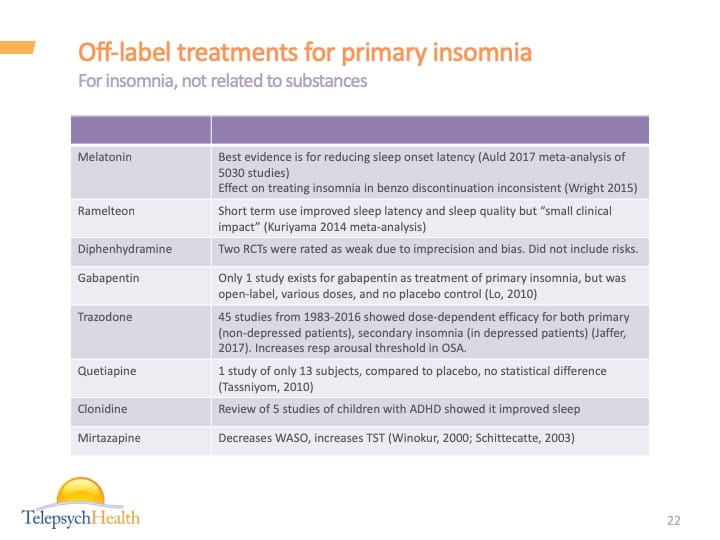

Off-label treatments for primary insomnia

For insomnia, not related to substances

Over the counters: Antihistamines, melatonin, valerian root (low risk, and little evidence that they are helpful)

FDA approved for sleep: Benzos (high risk, moderate evidence), suvorexant (Belsomra, high risk no evidence), ramelteon (low risk, 1 open label trial for AUD), doxepin (low risk, no evidence), z-drugs.

Avoid benzos as there is no RCT for SUD patients, there is abuse potential, and dangerous when mixed with alcohol, opioids.

FDA approved but not for sleep: melatonin, hydroxyzine, doxepin, gabapentin, trazodone, prazosin, quetiapine.

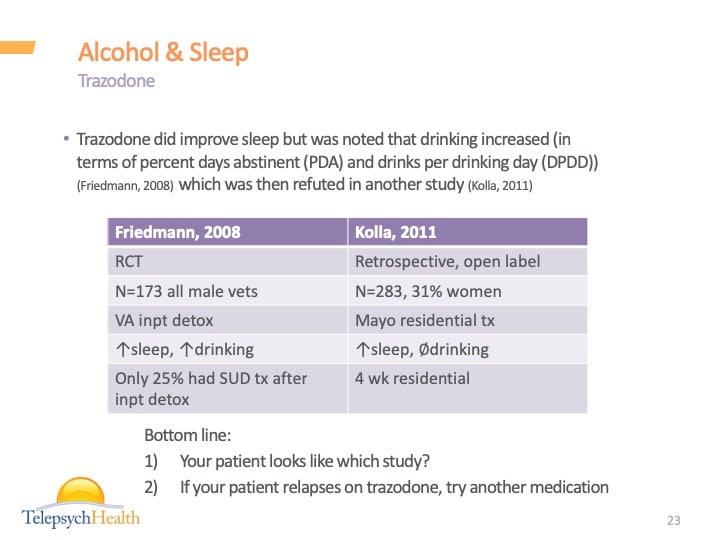

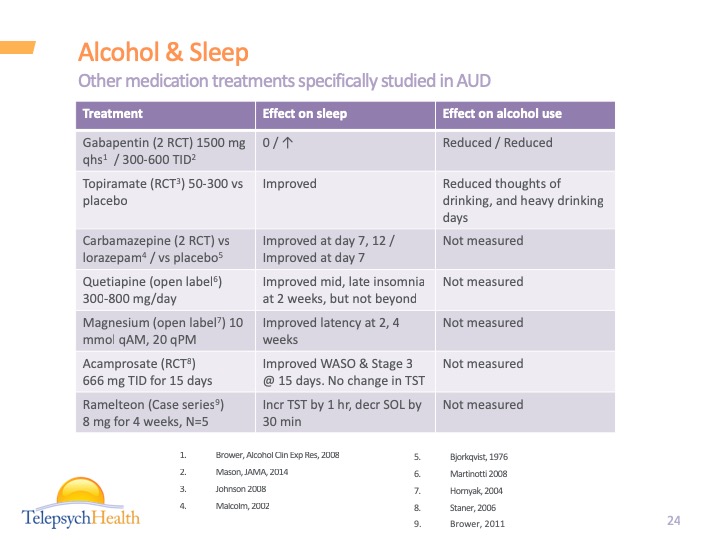

Alcohol & Sleep

Trazodone did improve sleep but was noted that drinking increased (in terms of percent days abstinent (PDA) and drinks per drinking day (DPDD)) (Friedmann, 2008) which was then refuted in another study (Kolla, 2011)

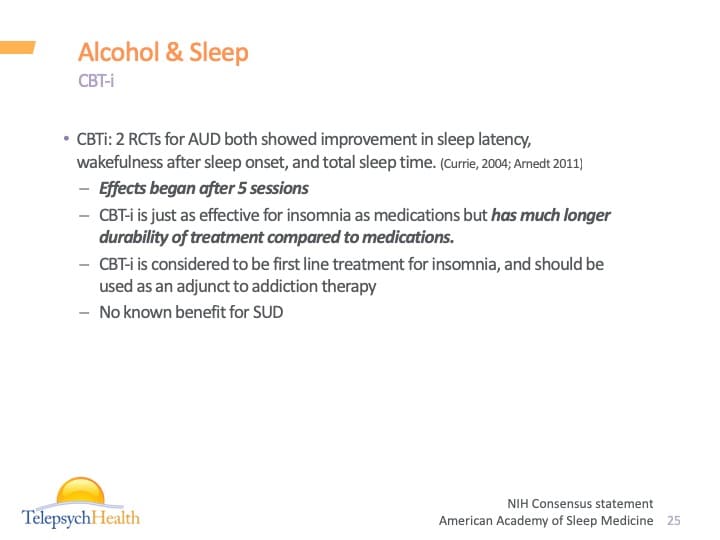

CBTi: 2 RCTs for AUD both showed improvement in sleep latency, wakefulness after sleep onset, and total sleep time. (Currie, 2004; Arnedt 2011)

Effects began after 5 sessions

CBT-i is just as effective for insomnia as medications but has much longer durability of treatment compared to medications.

CBT-i is considered to be first line treatment for insomnia, and should be used as an adjunct to addiction therapy

Appropriateness of CBT-i: is another condition present (insufficient sleep syndrome)?

Motivation level to do CBT?

Major component of CBT-i is sleep restriction, and is contraindicated in those with bipolar, untreated sleep apnea, parasomnias, and seizure disorder.

Typically 4-8 weekly treatment sessions.

Bed becomes a cue for not sleeping. Goal is to unpair the two and reduce the conditioned arousal associated with the bed.

What does CBT-i consist of?

- sleep hygiene & education

- relaxation training

- stimulus control

- sleep restriction

- cognitive therapy

Review sleep diary, educate about sleep drive, circadian rhythms.

PPP Model: Sleep disturbances consists of predisposing factors (anatomical abnormalities, genetics), precipitating factors (acute stressors), and perpetuating factors (napping, oversleeping, too much time in bed, sleep-related stress, conditioned arousal)

Only use your bed for sleep (associate the bed with sleep as much as possible). Goal = maximize sleep efficiency

If unable to fall asleep within ~30 min, get up and go to a dimly lit room and do something boring not involving a screen. Don’t do something too activating or engaging (don’t exercise, eat, smoke, take warm showers or baths at this time).

Do this as often as necessary throughout the night if you wake up at night.

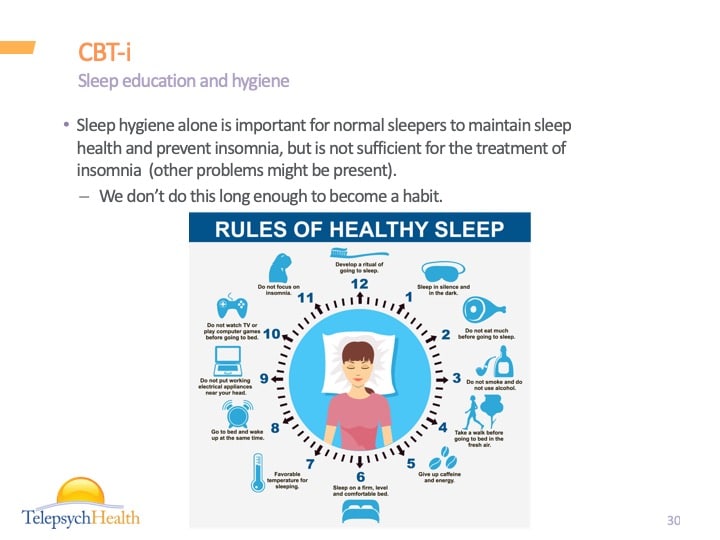

Sleep hygiene alone is important for normal sleepers to maintain sleep health and prevent insomnia, but is not sufficient for the treatment of insomnia (other problems might be present).

We don’t do this long enough to become a habit.

Aim: shift focus away from trying to relax, to focusing on engaging in an activity that promotes relaxation as a side effect.

Examples:

- Diaphragmatic breathing

- Progressive muscle relaxation

- Imagery

- Relaxation Training

Aim: increase homeostatic sleep drive and decrease time in bed awake

Example:

Usual schedule 10:30 pm to 6:30 am

But sleep diary shows sleeping only 5 hrs per night

New schedule: 1:30 am to 6:30 am

When sleeping close to 5 hrs, new bedtime becomes 1:15 am…. 1:00 am… 12:45 am…

We will have a period of doing well, followed by a high stress situation (travel, pain, work), which causes them to overcompensate for sleep loss by sleeping in, napping, or getting worried about sleep.

Goal is to identify those high risk situations, and come up with strategies for preventing these situations from becoming a relapse.

Address misinformation, avoidance behaviors, misattribution.

Misinformation: sleep myths (“drinking will help me sleep”)

Avoidance behaviors: cancelling activities due to feeling too tired, developing rigid sleep schedules

Misattribution: ”I will bomb tomorrow if I don’t get good sleep!”

Cognitive therapy and relapse prevention

Opiates & Sleep

Opioids suppress respiratory pacemaker at pre-Botzinger nucleus, decreasing respiratory rate and depth (predisposing to central sleep apnea)

Opioids decrease chemosensitivity to hypoxia/hypercapnia

Opioids decrease genioglossus activity (controlling tongue protrusion/retraction, elevation/depression), increasing upper airway resistance.

Opioids decrease upper airway dilator muscle activity, thus increasing pulmonary resistance

Decreases phrenic nerve and diaphragm muscle activity

Cause very irregular tidal volumes (Biot’s respirations)

75% of patients on opiates have sleep disordered breathing (Walker, 2007)

39% have obstructive sleep apnea

24-30% had central sleep apnea (opiates are the 2nd most common cause of central sleep apnea after heart failure)

8% had both

In other studies of patients on opiates (Lee-Ionotti, JSCM, 2014, Wang Chest 2005)

75-85% of patients on chronic opiates had mild sleep apnea or greater.

36-41% had severe sleep apnea

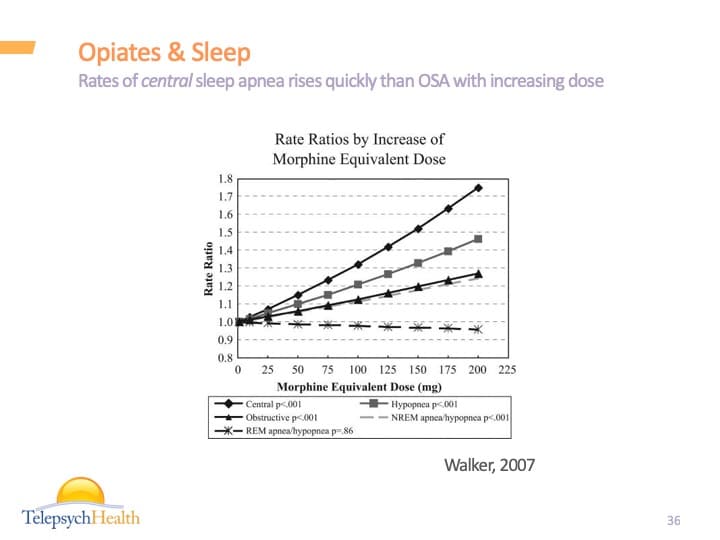

Rates of central sleep apnea rises quickly than OSA with increasing dose

Suboxone and ataxic breathing study during inpatient stay (N=70, Farney, 2013)

63% with at least mild sleep apnea, 16% of which was moderate sleep apnea, and 17% severe sleep apnea

73% irregular breathing patterns, 39% of which was severe.

Age 31 ± 12, non-obese (BMI 24), and female (60%), in LDS hospital in Salt Lake City, UT.

Limitations: could be argued that the disordered breathing is residual from prior opioids. The degree of hypoxemia at elevation (1500m) might be more pronounced. The study was done 48 hrs after initiating bup, so longer term impact is unknown.

Effects on breathing are also seen with suboxone

Opiates & Sleep

No medication found to be beneficial to reverse opiate related sleep problems.

In cases/small studies, acetazolamide helps OSA (works better in heart failure patients), ampakines improved O2 saturation and the hypercapnic ventilatory response

For CPAP, a study showed AHI index reduce from 44 to 14

For BiPAP, cases show some effectiveness, studies show improved apnea but persistent hypoxemia.

There are 4 case reports showing that opioid breathing abnormalities is reversible with opioid reduction or withdrawal but can last 3-5 months.

Occurs in people who have OSA, and are treated with BiPAP or CPAP and subsequently develop CSA. Occurs more in individuals on opiates as they have a tendency toward CSA.

Given that CPAP/BiPAP may be ineffective or worsen CSA in patients who use opioids, use Adaptive Servo-Ventilation (ASV).

ASV: detects reductions or pauses in breathing and then delivers a breath (if needed) to maintain >90% of the patients normal breathing rate.

Similar to BiPAP but adjusts IPAP and EPAP on each breath

In CSA patients, 5 of 6 studies showed using ASV leads to reduction of AHI and central apnea index.

Complex sleep apnea = “CPAP emergent”

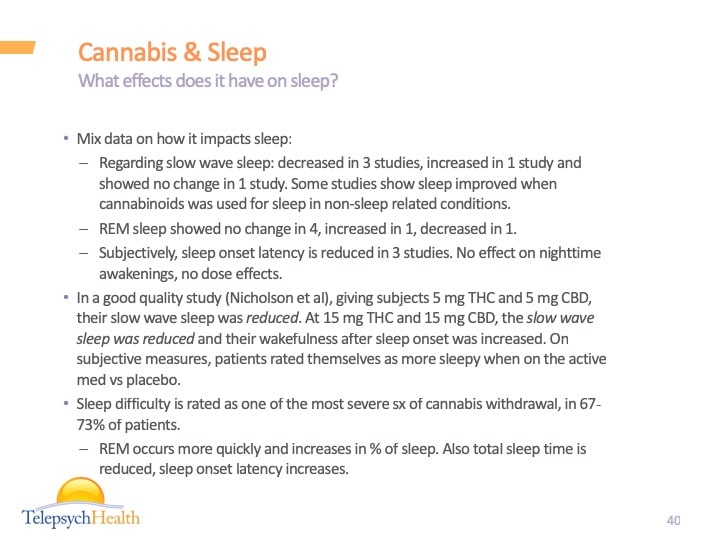

Cannabis & Sleep

Mix data on how it impacts sleep:

Regarding slow wave sleep: decreased in 3 studies, increased in 1 study and showed no change in 1 study. Some studies show sleep improved when cannabinoids was used for sleep in non-sleep related conditions.

REM sleep showed no change in 4, increased in 1, decreased in 1.

Subjectively, sleep onset latency is reduced in 3 studies. No effect on nighttime awakenings, no dose effects.

In a good quality study (Nicholson et al), giving subjects 5 mg THC and 5 mg CBD, their slow wave sleep was reduced. At 15 mg THC and 15 mg CBD, the slow wave sleep was reduced and their wakefulness after sleep onset was increased. On subjective measures, patients rated themselves as more sleepy when on the active med vs placebo.

Sleep difficulty is rated as one of the most severe sx of cannabis withdrawal, in 67-73% of patients.

REM occurs more quickly and increases in % of sleep. Also total sleep time is reduced, sleep onset latency increases.

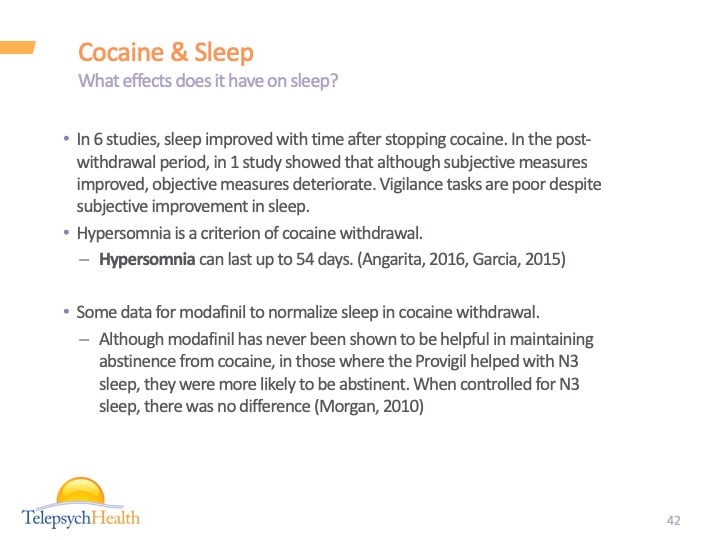

Cocaine & Sleep

In 6 studies, sleep improved with time after stopping cocaine. In the post-withdrawal period, in 1 study showed that although subjective measures improved, objective measures deteriorate. Vigilance tasks are poor despite subjective improvement in sleep.

Hypersomnia is a criterion of cocaine withdrawal.

Hypersomnia can last up to 54 days. (Angarita, 2016, Garcia, 2015)

Some data for modafinil to normalize sleep in cocaine withdrawal.

Although modafinil has never been shown to be helpful in maintaining abstinence from cocaine, in those where the Provigil helped with N3 sleep, they were more likely to be abstinent. When controlled for N3 sleep, there was no difference (Morgan, 2010)

Tobacco & Sleep

Tobacco use and withdrawal can cause insomnia.

Individuals who use chronically have 2x higher rate of insomnia compared to general pop, especially difficulty falling asleep.

Insomnia is also a withdrawal symptom, starts in 6-12 hrs after last use, peaks in 1-7 days, and can last 3 weeks. Insomnia is also associated with relapse to smoking.

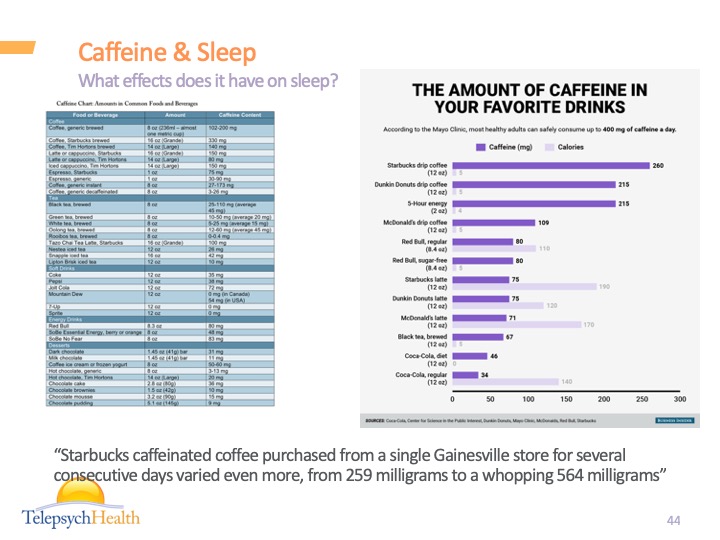

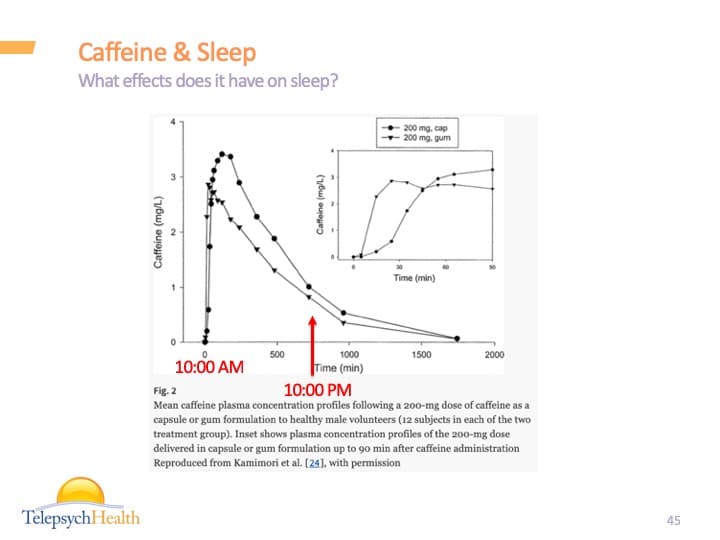

Caffeine & Sleep

What effects does it have on sleep?

Evening intake of 200 mg caffeine (divided evenly between 1 and 3 h before bedtime) increased sleep latency by 7 min, reduced sleep efficiency by 5%, and decreased sleep duration in younger (23.8 y) adults and older (50.3 y) adults (Drapeau, 2006)

In a slightly older age group (mean age: 56), 300 mg caffeine decreased total sleep time by an average of 2 h and increased mean sleep latency to 66 min. The number of awakenings increased as did the mean total episodes of intervening wakefulness, particularly during the last 3 h of sleep. Stage-2 sleep was increased, whereas SWS was reduced in the first 3 h of sleep. No significant change was observed in REM sleep. (Brezinova, 1974)

Genetic variants in adenosine receptor gene can cause vast differences in response to caffeine.

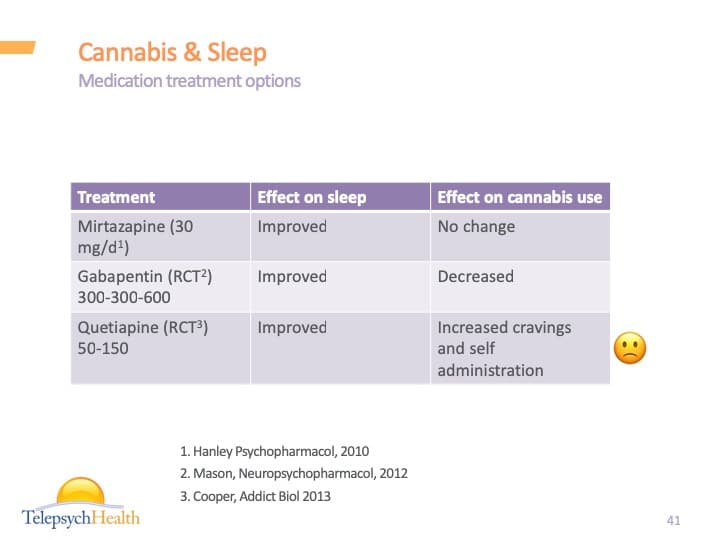

Summary of Treatments for Insomnia

Reasonable medication options

Melatonin or hydroxyzine (rx)

Doxepin (FDA approved)

Gabapentin (off-label) if AUD or CUD

Trazodone (careful with AUD)

Prazosin with comorbid nightmares (off-label)

Clonidine with comorbid ADHD sx (off-label)

Quetiapine (unless with CUD)

Mirtazapine with comorbid depression, anxiety (off-label)

Topiramate if AUD

Please note that the information provided on this website is not medical advice. It is only for informational and educational purposes.